Independent reading is the practice of reading by students. Reading is a skill that requires practice and therefore independent reading is a key component of a balanced literacy program. Just as a child learns to swim by swimming and to play the piano by playing, children need to read in order to get better as readers. Acclaimed author, educational consultant and researcher Richard Allington (2001), found a direct correlation between the amount of time spent reading and reading performance. Allington emphasizes that in order for children to progress as readers, they need to read with volume, stamina and fluency.

As part of a balanced literacy program, students have time daily to read independently during the reading workshop. The heart of a balanced literacy environment is the classroom library which has a variety of texts for students to read that range in reading difficulty, genre, author and topic. While reading texts, students are independently applying the fluency, comprehension and word attack strategies that are modeled and explicitly taught during interactive read aloud, shared reading, guided reading and reading strategy groups.

The materials students read for independent reading are those they select from the classroom library. The self-selection process of independent reading places the responsibility for choosing books in the hands of the student which teaches them that they have the ability to choose their own reading materials and that reading independently is a valuable and important activity. Students are taught how to choose appropriate texts referred to as "just right books" (i.e., texts that are at their independent reading level).

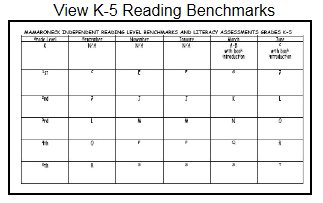

Teachers use a variety of informal and formal methods to assess students' independent reading levels. Many teachers use running records to determine independent reading levels of students. A running record is a valuable assessment tool because it assesses fluency, comprehension and word accuracy. The independent reading level of a student is the level that he/she reads with 96% to 100% accuracy as well as with fluency and comprehension (e.g., literal, inferential, interpretive). By matching students with texts that are appropriate, students are able to read with volume (i.e., many texts), stamina (i.e., longer periods of time) and fluency - the habits of proficient readers.

Most importantly is that by reading independently a student becomes confident, motivated and enthusiastic about his/her ability to read.

- Allington Research Overview on Volume and Stamina

- Allington Guidelines For Volume Across the Levels

- Fountas and Pinnell Strategic Actions of Comprehension

- Harvey Comprehension Continuum

- Fountas and Pinnell Fluency Rubric

- Fountas and Pinnell Oral Reading Rates

Attachments:

Professional Article Emergent Reading

Yearlong Class Independent Reading Levels Data Collection Template

Yearlong Class Phonemic Awareness Data Collection Template

Allington, R. (2001). What Really Matters For Struggling Readers. New York, NY: Longman.

Calkins, L. (2000). Art of Teaching Reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Collins, K. (2004). Growing Readers: Units of Study in the Primary Classroom. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Goldberg, G. & Serravallo, J. (2007). Conferring with Readers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Miller, D. (2002). Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Routman, R. (2002). Reading Essentials. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Sibberson, F. & Szymusiak, K. (2003). Still Learning to Read: Teaching Students in Grades 3-6. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Taberski, S. (2000). On Solid Ground: Strategies for Teaching Reading K-3. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.